NYC Needs Congestion Pricing, But Critics Have a Point Too…

Post-pandemic traffic congestion has been especially prevalent in neighborhoods outside of Manhattan, such as South Bronx. (Image Source: Yuvraj Khanna for the New York Times)

By Eric Pu

Cars. These climate-controlled hunks of metal on wheels transport hundreds of millions of Americans on a daily basis, and it’s straight up impossible to conceive of a New York entirely devoid of personal automobiles. At the same time, their presence is no doubt disastrous for the local environment—a Harvard study estimated that cars are responsible for 1400 premature deaths in the New York area annually, and that’s through pollution alone. Cars are also hazardous to pedestrians, and are a primary contributor to the city’s noise. Add to that the fact that the city’s roads are readily prone to congestion, making it difficult for trucks carrying essential goods or buses carrying armies of commuters to reach their destinations on time, and it’s evident that cars have an adverse effect on the quality of life of many New Yorkers.

Thus, as part of a long-standing effort to combat traffic congestion in the nation’s economic capital, the Department of Transportation has proposed a new plan titled the Central Business District Tolling Program, colloquially referred to as “congestion pricing.” If implemented, this new program would charge all vehicles a flat rate to enter the Central Business District (or CBD, defined as all of Manhattan below 61st Street, excluding the highways around its edges.) This plan has the potential to bolster overall economic productivity in the New York metropolitan area as a whole, whilst improving the efficiency of public transportation and diminishing pollution, improving quality of life for many. However, that is not to say that congestion pricing is perfect, and it’s certainly possible that its most vocal critics may actually have a valid argument against its implementation.

A diagram of the proposed “Central Business District”—the area affected by congestion pricing. (image Source: New York Times)

The proposal is complex, and some additional context is necessary to fully comprehend it. To begin, the affected Central Business District sees 7.7 million individuals entering on any given weekday, with 75% of them arriving via public transportation, and 24% through an automobile. Thus, despite having the most extensive and robust public transportation network in the entire country, this sheer volume equates to New York City’s traffic continuing to rank as the #1 worst in all of America. Such congestion inevitably brings serious social and economic repercussions, with the USDOT estimating a grand total of 102 hours of lost time, or close to $1600 per year in economic opportunity cost, suffered per driver in the NYC region. Congestion also limits the efficiency of bus speeds in the CBD, which have declined by 28% since 2010. Beyond commuters, traffic interrupts the flow of emergency vehicles, raises costs of delivery services, and overall makes conducting business in the area costly and difficult.

The proposals for congestion pricing include a whole slew of different potential toll rates, with the highest being up to $23 during peak hours whenever a vehicle enters the CBD. Extrapolate that number throughout a month’s worth of workdays, and commuters could be facing up to $600 per month worth of congestion charges. This would serve as a massive source of new revenue to the city of New York, with an estimated $1 billion in fees being directed solely towards the MTA—a number that would certainly put a sizable dent in the transportation agency’s current deficit of $2.7 billion.

A chart showing the highest and lowest proposed rates for congestion pricing. (Information Source: Metropolitan Transportation Authority; Image Source: New York Times)

Although support has been widespread amongst residents of Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens, congestion pricing has attracted a number of critics from those who reside in other boroughs or adjacent regions of New York. South Bronx Rep. Ritchie Torres, a self-proclaimed “former congestion pricing advocate,” stated that his borough felt "ambushed" as these current proposals would simply redirect existing Manhattan traffic to The Bronx instead, claiming “The Bronx is [already] the most congested and polluted place.”

Push-back has been especially vigorous in Staten Island, where local congressional representative Nicole Malliotakis has placed immense pressure on Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg to mandate the completion of a full Environmental Impact Statement and Economic Impact Study on the project. Staten Island is the sole borough of New York where the majority of residents (64%) commute via car—meanwhile, only 8% of Manhattanites drive to work.

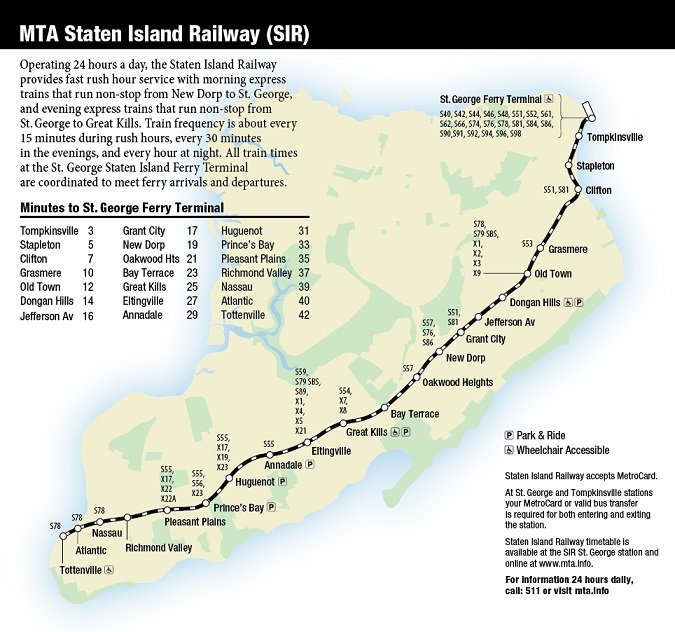

A map of the Staten Island Railway. (Image Source: Metropolitan Transportation Authority)

Although it’s easy to consider driving as a luxury in New York, the harsh reality is that for some city residents using a car is the only reliable way to commute to work. Public transportation in Staten Island is substantially worse than the other four boroughs, and getting from the island to Manhattan can be especially difficult. Adding an extra several hundred dollars worth of tolls per month, on top of an already tedious and long commute, just to use city infrastructure that you’ve already paid for via city taxes is understandably frustrating.

Rep. Malliotakis also raises an interesting point regarding the problem with funding the MTA as a whole, previously describing the agency as a financial “black hole.” Although the MTA is no doubt essential to New York, it cannot be disputed that there is a high amount of tax dollar waste stemming from the city’s public transportation. The on-going 2nd Avenue Phase 2 project, which brings much needed extensions up into East Harlem on the Q line, has a total cost currently estimated at $6.4 billion for 1.8 miles of track, at a rate of $3.6 billion per mile—far and away the most expensive subway project in the world by price per distance. Earlier this May, the MTA was under fire for spending an astounding $30 million for the construction of a single staircase in the Times Square subway station.

Couple this with the recent fear of crime in the city’s subway system, which ranked first in riders’ concerns this year, and commuters might not necessarily be interested in ditching their cars for a train. So long as the MTA fails to misuse its funding, or adequately address safety concerns, some New Yorkers will continue to be hesitant about shouldering the immense cost of congestion pricing just to fund public transportation.

Eric Pu is a junior at New York University, studying economics and public policy. Hailing from Toronto, Canada, he is deeply interested in the issues of public transportation and its role in urbanism. He most recently interned at the US Department of Transportation in Washington D.C.